Mozoomdar at Sea

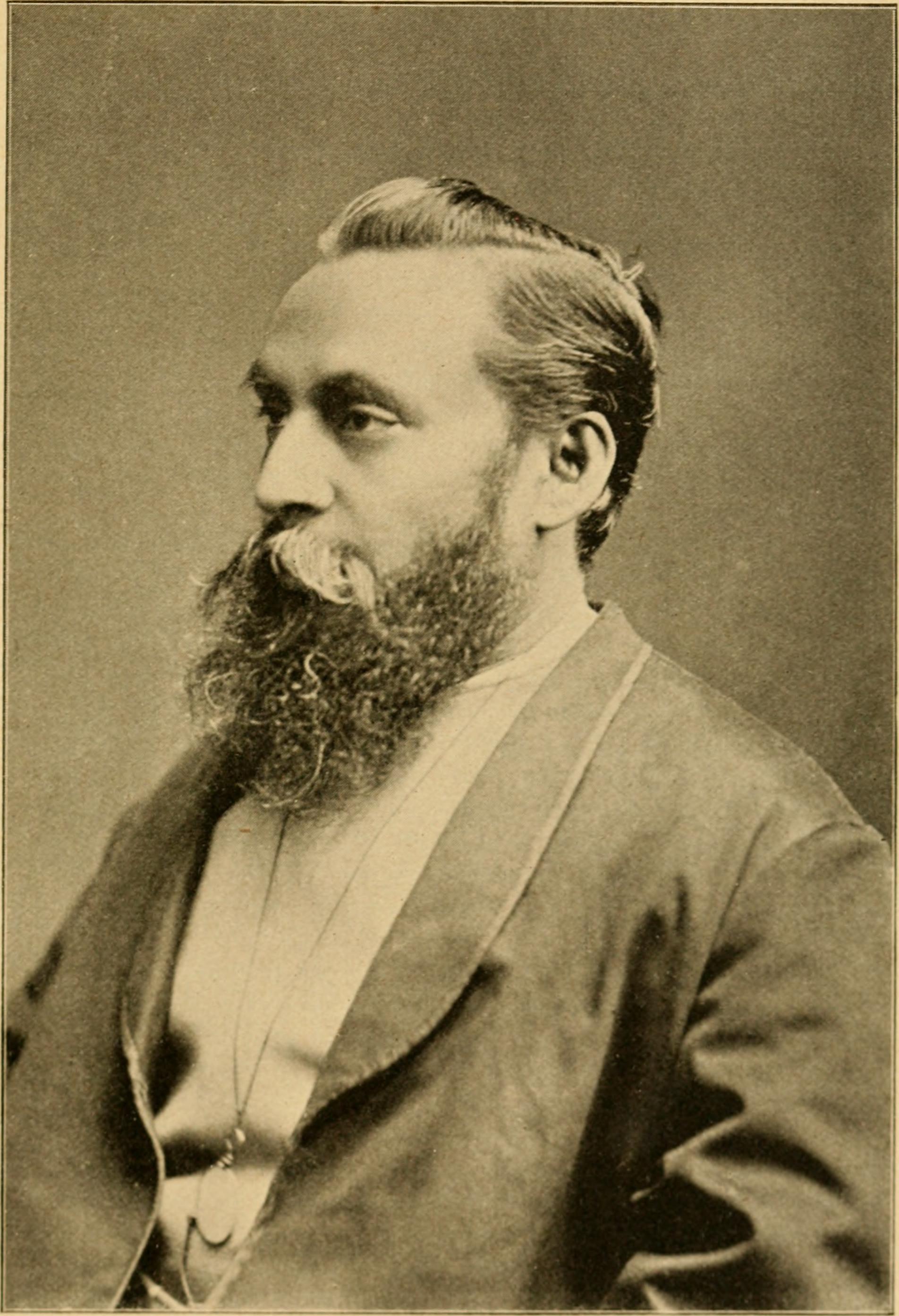

Protap Chunder Mozoomdar (PCM) was one of the first Indians to command an audience in the United States of America, perhaps best-known for his participation in the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. A prominent member of the Brahmo Samaj, a Bengal-based community of Hindu reformers, Mozoomdar first captured the imagination of Europeans and Americans in 1883. At that time, his lectures across America’s eastern seaboard (not to mention the publication of his book, The Oriental Christ) enamored liberal Christians such as Jenkin Lloyd Jones, a Unitarian minister who would help organize the World’s Parliament of Religions to be held in conjunction with the Chicago World’s Fair.1 PCM attended and addressed this parliament in order to rally support for the New Dispensation, a Brahmo Samaj project of global religious confraternity that he hoped would mark the end of religious sectarianism and restore the prominence of an emotional, rather than intellectual, pursuit of God.

Protap Chunder Mozoomdar

This project sketches Mozoomdar’s journey to the 1893 World’s Fair. It is based principally on correspondence to his wife, Saudamini, translated into English from Bengali originals. These letters offer intimate glimpses of human vulnerability, hope, and ambition within the person of PCM. I document this perspective to contribute, however humbly, to the history of this often-overlooked religious figure. Mozoomdar is often eclipsed by the dueling shadows cast by Swami Vivekananda and Keshub Chunder Sen, his more bombastic contemporaries, to the extent that he has seldom been the subject of his own story. By attending to Mozoomdar’s private life in the months that prefaced his addresses at the World’s Parliament of Religions, “Mozoomdar at Sea” offers a view of the broader context in which PCM prepared his Chicago lectures, and articulated his hopes for the “New Dispensation,” the Brahmo Samaj’s vision of a future wherein humankind would unite in one encompassing religion.

Kolkata

Protap Chunder Mozoomdar gave a farewell address to his Brahmo Samaj congregation on Sunday evening, July 9, 1893.2 Delivered two days before his departure for the World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago, Mozoomdar’s speech is ridden with hopes and fears no doubt heightened by what he felt to be a call from God to fulfill the prophecy of global religious unity pronounced by his late friend and mentor Keshub Chunder Sen.3 Before the danger of a long sea journey, PCM worried aloud over his frail health, ability to glorify God, and the loneliness of his wife Saudamini, who would stay behind in Kolkata. He sought from his listeners both prayers for his wellbeing and the cessation of their sectarian quarrels. Saddened by the past decade of conflict within the Brahmo Samaj, PCM called for peace among its factions, the inner strife of which threatened any chance for the united theistic brotherhood he hoped would result from the World’s Parliament of Religions. As will be seen, these concerns followed Mozoomdar throughout his westward journey.

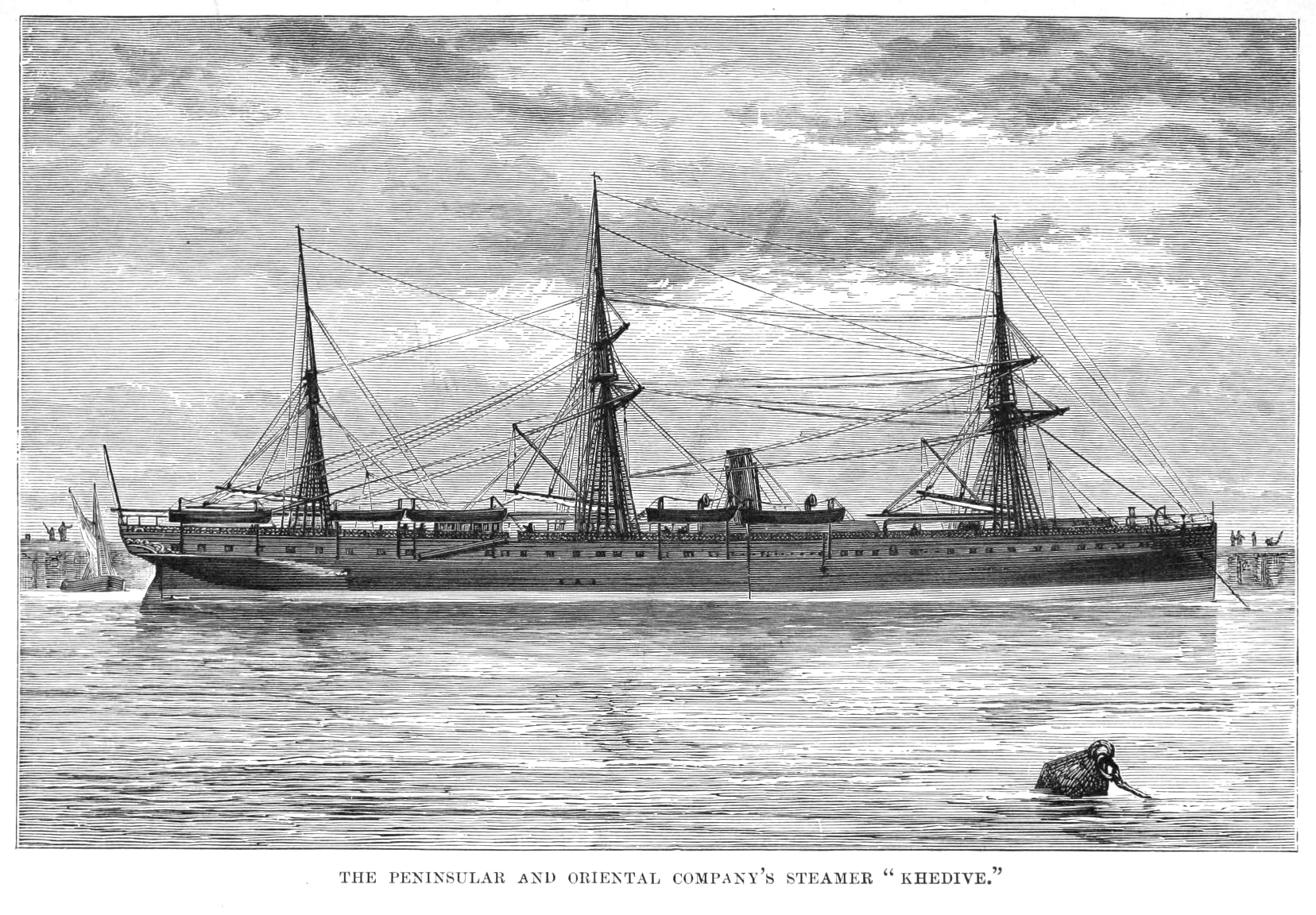

P&O Steamship Khedive, 1871

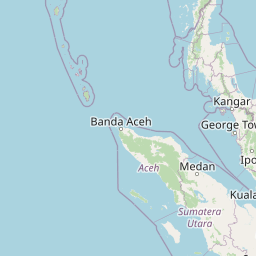

At 11:30am on Tuesday July 11, 1893, Mozoomdar boarded the P&O steamship Khedive headed to London, the first leg of his journey to Chicago. According to a Brahmo Samaj newsletter, “enthusiastic shouts, the waving of handkerchiefs and the sincere prayers of his friends and sympathizers” animated the gathering of over 100 people at a Kolkata pier that morning.4 Unfortunately for Mozoomdar, the energy of this farewell was not enough to propel the ship very far. In a letter to Saudamini, he complained that the SS Khedive had traveled only a few miles from the jetty before halting for 20 hours in the Garden Reach shipyard, affording no sleep due to the heat.5 This was followed by a full day’s delay at Diamond Harbor, the port at the mouth of the Hooghly River. It was not until noon on July 13 that Mozoomdar tasted the salty air of the Bay of Bengal.

Bay of Bengal

Mozoomdar spent three days traversing the bay. The letters he wrote to Saudamini during this time reveal a man enraptured by the beauty of the sea, which he took to be proof of God’s immanent presence. Consider his first impressions of the waters before him:

The endless expanse of rippling blue is like the open arms of a mother. The dancing, churning waves crowned with surf are like excited children, and I their brother whose sight has filled them with joy, encouraging me to dance, chanting the name of Goddess Anandamayi.6

Yet Mozoomdar’s prose never strays too far from matters of health, and the account of his first days at sea is ridden with descriptions of medications and reflections on his constitution. Although expressed as assurances to Saudamini of his healthiness, Mozoomdar’s preoccupation with details such as whether he slept through the night, the pain in his hand, his regular consumption of cod liver oil, and his upset stomach suggests that he continued to worry over his physical condition.7

Dark red waves at the hull give way to ropes of surf embracing the coast of Sinhala. And then shores of white sand, leading up to the dark jungles of palm trees. Behind all, mountains tear the bosom of the sky. Only in the golden Lanka can a sight like this be seen. Pearls are strewn about everywhere in the seabed. Corals, gems, sandalwood, ivory, ebony, all you can wish for, as much as you need. Coconuts and areca palms are floating in the gentle waves. Everything is available, but the presence of God and true devotion to religion is rare.8

Mozoomdar’s description during his approach to Sri Lanka emphasizes two of his religious convictions. First, that the mark of God is manifest in all of the beauty and power of nature. Second, that despite abundant signs of divine presence, many have lost touch with the spirit of God.9

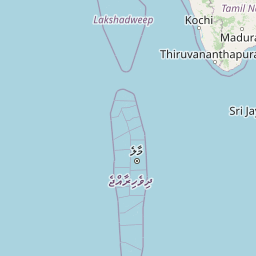

Colombo

PCM stopped for two days in Colombo, welcomed with generosity by Anagarika Dharmapala, the famous Buddhist revivalist who would also speak at the World’s Parliament of Religions. In a letter to Saudamini, Mozoomdar extolled the monk’s kindness for allowing him to board in his father’s house, feeding him a feast of fresh fruits and vegetables, and attending to his insomnia by providing good conversation throughout the night.10

Anagarika Dharmapala, 1893

Arabian Sea

Mozoomdar returned alone to the SS Khedive, for Dharmapala had other travel arrangements. Over the next week-and-a-half amid the throes of the Arabian Sea, he wrote to his wife nearly every day. Though several of Mozoomdar’s letters express longing for Saudamini’s voice and cooking, his sharpest desire appears to have been to micromanage her life, even from afar.

In a telling sequence, he backtracks from the sentiment that his journey might allow Saudamini some rest from her wifely duties by proceeding to barrage her with rhetorical questions to the effect that she constantly apply herself toward sacred conduct.11 In another passage, his very desire to hear from her, far from the heartfelt pleas found in Indian love stories, becomes another attempt to control her lifestyle: he writes, “news of your happiness, your wellbeing, your following the Brahma-vrata12 like I did, you getting along with everyone around you will help my work profoundly."13 The intimacy among these letters is, predictably for this period, that of a husband who assumes the right to control his wife’s affairs.14

Saudamini Mozoomdar, c.1890

Yet his letters during this period tell of more than a husband at pains to assert power over his wife. Mozoomdar often wrote of cloudless days of sultry heat and stormy nights that rattled the ship and its passengers. Though he insisted he never felt seasick and declared that the ocean voyage made him stronger, PCM complained of poor health during this stretch of travel: the heat kept him from sleep, the wind and the dampness made him feel ill, and he could not shake the pain from one of his hands.15

These rapid transformations in the weather did more than affect his health. On his third day out from Colombo, Mozoomdar wrote to Saudamini of black waves tearing into the hull of the SS Khedive in the manner of cannonballs and sheets of rain that transformed nature itself into the terrifying form of the goddess Bhairavi.16

Inspired by the tempest, Mozoomdar wrote an article for The Interpreter, a Kolkata-based journal he edited. The refrain in this piece, titled “The Raging Sea,” as well as in his letters to Saudamini at this time, is to seek refuge in God, for “the unerring of the great Captain shall steer us to the harbor duly."17 More than fear of domestic powerlessness, Mozoomdar’s consistent calls for trust in God’s will to both Saudamini and the readers of The Interpreter suggest a desire to maintain social ties with loved ones in the way he knew best - by preaching God’s presence. As will be shown, Mozoomdar felt more and more lonely en route to London.

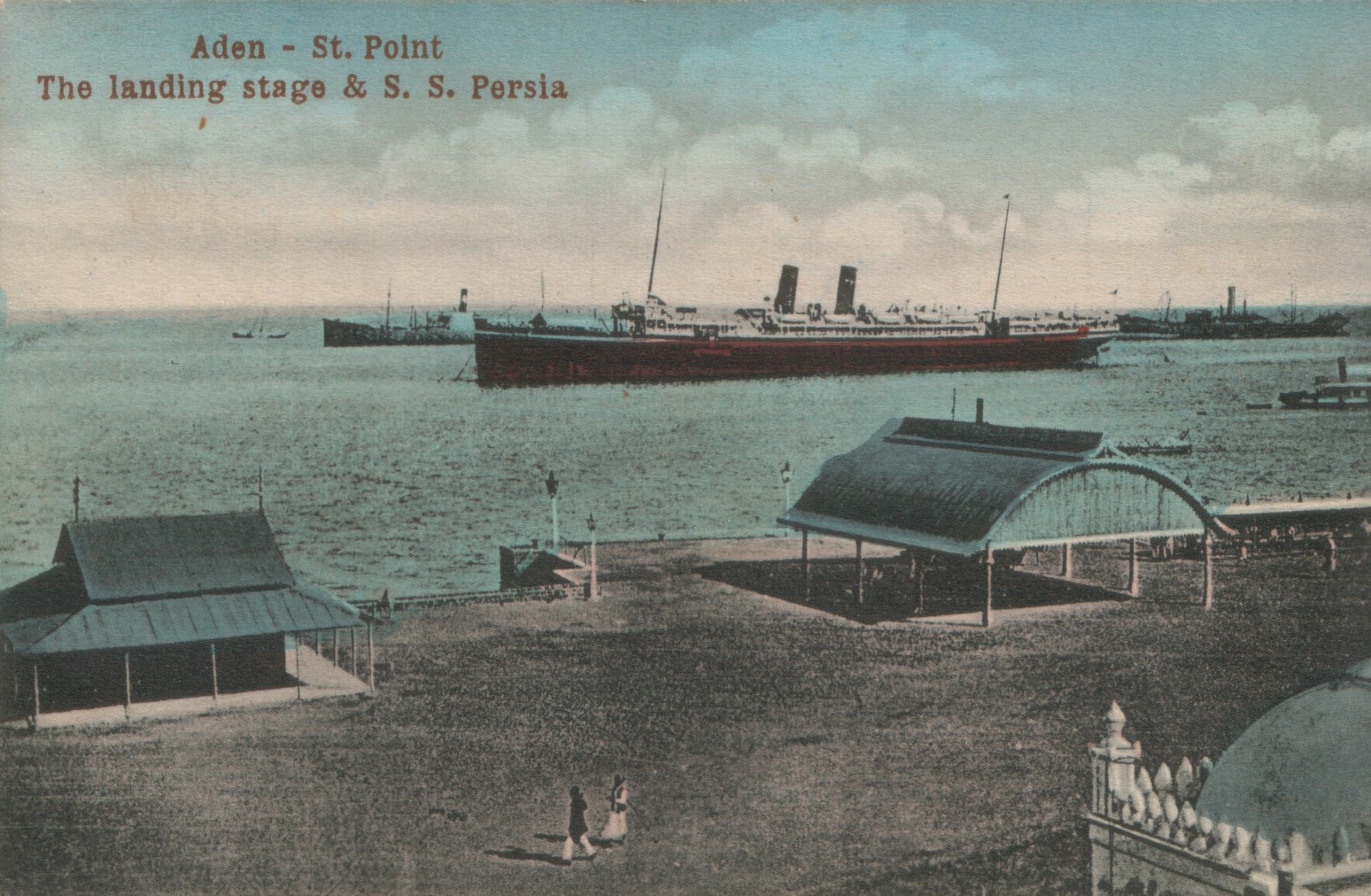

Aden

After a stretch of ten days at sea, PCM arrived in Aden on 28 July. Instead of the excitement one might expect from someone finally able to stretch his legs, his letters give evidence of a man pained at the distance from his loved ones. After receiving and reading his first batch of reply mail from the port city, Mozoomdar gushed over the chance to read his wife’s writing:

Only you can write this way. I feel blessed to read it. I read it again and again. I plan to read it more during my journey…. No matter how low a husband is, the dutiful care of his wife will lead to her own greatness. I hope I can someday become worthy of your love and respect.18

Compare that excitement with his distaste for the crowds of Aden: “I have never been one for company. I don’t like the babble of people. I am lonely in the truest sense of the term, waiting patiently to gain His eternal company."19 Again, the unhappiness of Mozoomdar’s solitude manifests a longing for proximity to God.

Postcard of Aden's St. Point landing, c.1910

Mozoomdar had cause to feel lonely. For the past decade, he had been struggling to reconcile the warring Brahmo Samaj factions in the wake of Keshub Chunder Sen’s controversies and death, with little success. Bereft of his friend and alienated from other Brahmos because of that friendship, PCM became the object of scorn by many Brahmos who felt threatened by the idea that he might try to succeed Keshub as leader of the group.20 For Mozoomdar, whose global aspirations for the Brahmo Samaj and its New Dispensation were more pronounced than most, the opportunity to leave such squabbles behind in order to bring Keshub’s vision to life in the West was surely a welcome one.

Red Sea

Yet Mozoomdar expressed disappointment in the behavior of his shipmates. In a piece he wrote for The Interpreter, titled “Red Sea, Why Red,” PCM suggested that the Red Sea was so-named because of the excruciating heat experienced when traveling its waters. With tongue in cheek, he added that even “the freezing attitude of his fellow passengers” could not cool him down.21 Though there is no evidence that anyone treated him poorly at sea (to the contrary, he described being pampered by a British servant named Harris, who massaged him with medicinal oils),22 PCM expressed to Saudamini that religious life aboard the ship did not meet his expectations. After several Sundays without the promised religious services, Mozoomdar resigned himself to dissatisfaction, writing “it turns out that neither Kolkata nor this ship can afford me those luxuries."23 Without friends or occasions for religious fulfillment, and sweltering in the sun besides, Mozoodmdar was not at his best upon the Red Sea.

Suez Canal

The Suez Canal, 1894

At the height of his suffering Mozoomdar scribbled, “it’s too hot to write any more. I will just close my eyes for some time."24 By the end of his five days on the Red Sea, PCM was covered in heat rashes and found it difficult to breathe.25 In the delirium of his condition, Mozoomdar mistook Port Suez for Port Said and posted letters to Saudamini that he later apologized would likely arrive a full week later than planned. Fortunately, the worst of his journey was over. Immediately upon entering the Mediterranean, PCM wrote to his wife of relief: “All storms have subsided. All the heat is gone, too. All fears have been erased from my mind. The peaceful waters of Europe are making the wind cool and pleasant."26

Mediterranean Sea

More than a change of weather, these “European waters” marked a turning point in Mozoomdar’s living conditions and resolve. Having moved to a cabin further below deck that afforded him additional space and refuge from the summer sun, he resumed preparations for his lectures.27 PCM’s writing during this time indicates that he was preoccupied by issues of character. In a letter written to Saudamini, he lamented the difficulty of maintaining upright behavior amid the “luxury and sport and decadence” of those aboard the ship.28 Yet wariness of the passengers did not detract from Mozoomdar’s respect for the crew. In an article penned for The Interpreter, titled “The Organisation of a British Ship,” he lauded the captain and staff for so efficiently distributing and pursuing their responsibilities:

There is no interference, no idleness, no intention to deceive, no insolence, or insubordination. And that is the secret of Government, either in the church, or in the state, or in the household…. [Only then] can the bark of life steer on its onward course and reach in safety its remote destination.29

Here, as elsewhere, Mozoomdar saw in his surroundings the reflection of God’s teachings. Using the relationship of captain and crew as an example, he encouraged complete trust and obedience to God, the figurative captain at the helm of the “bark of life.”

P&O Steamship Khedive, c.1876

Marseille

Arriving on the evening of August 8, Mozoomdar spent two days sightseeing in the French town of Marseille. He described to Saudamini the mountain ranges, backwaters, and the “very pretty, clean, and cheerful” residents, who lack “the chalky whiteness that we find in the Englishmen."30 In contrast to the pallor of his shipmates, PCM had long since written to his wife of the healthful “red tinge” that the sea journey had left on his body.31 Although his letters indicate that he felt strengthened by the time spent in Marseille, Mozoomdar decided against inland travel through Europe to London for health reasons.32 Instead, he boarded the SS Khedive once again and set out toward the Strait of Gibraltar.

Marseille's Old Harbor, c.1890

Strait of Gibraltar

The fortress-ridden shores of Spain on one side and the mountain ranges of Africa, devoid of people or greens, on the other. We are sailing up the narrow stream in between. The water is peaceful, the wind is cool, and the sunlight feels beautiful. I am filled with hope, and the place of my work lies ahead of me.33

Though Mozoomdar never mentioned the Pillars of Hercules as he passed through the Strait of Gibraltar, they held true as a symbolic threshold to a utopian beyond. He believed the promise of the imminent New Dispensation lie in wait for him across the Atlantic. Yet Mozoomdar saw more than Chicago on the horizon. Though speedily approaching London, where he would give several sermons, PCM wrote to his wife of his future homecoming:

I will return home a new man. You will also probably be a new person by then. I won’t get angry at you or annoy you any more with my tedious intolerances. You will also not be angry at me or deride my actions. If God is near, this will be possible and we’ll know.34

Bay of Biscay

Mozoomdar indeed felt that God was near. As he traveled the Bay of Biscay, which he thought would be ridden with storms, he attributed his calm passage to “the grace of the Almighty."35 Yet God’s proximity stood in contrast to the ever-increasing distance separating Mozoomdar from his friends and family. Over a month had elapsed since his departure, and a letter to Saudamini shows that these loved ones often came to mind. A chair given to PCM by his friend Dr. Dutta in Kolkata was the object of much attention by the sailors, who fitted a small pillow to its headrest. Mozoomdar expressed gratitude for the chair, which helped him to sleep on nights when the stuffiness of his former cabin kept him awake. His recently improved health served as an occasion to hope for the wellbeing of his distant compatriots, whom he asked Saudamini to send his love. Even the luxurious lifestyle of the passengers reminded him of home, for it so starkly differed from the poverty he and his wife suffered in their early marriage.36 In sum, Mozoomdar’s anticipation of London was outpaced by nostalgia for home.

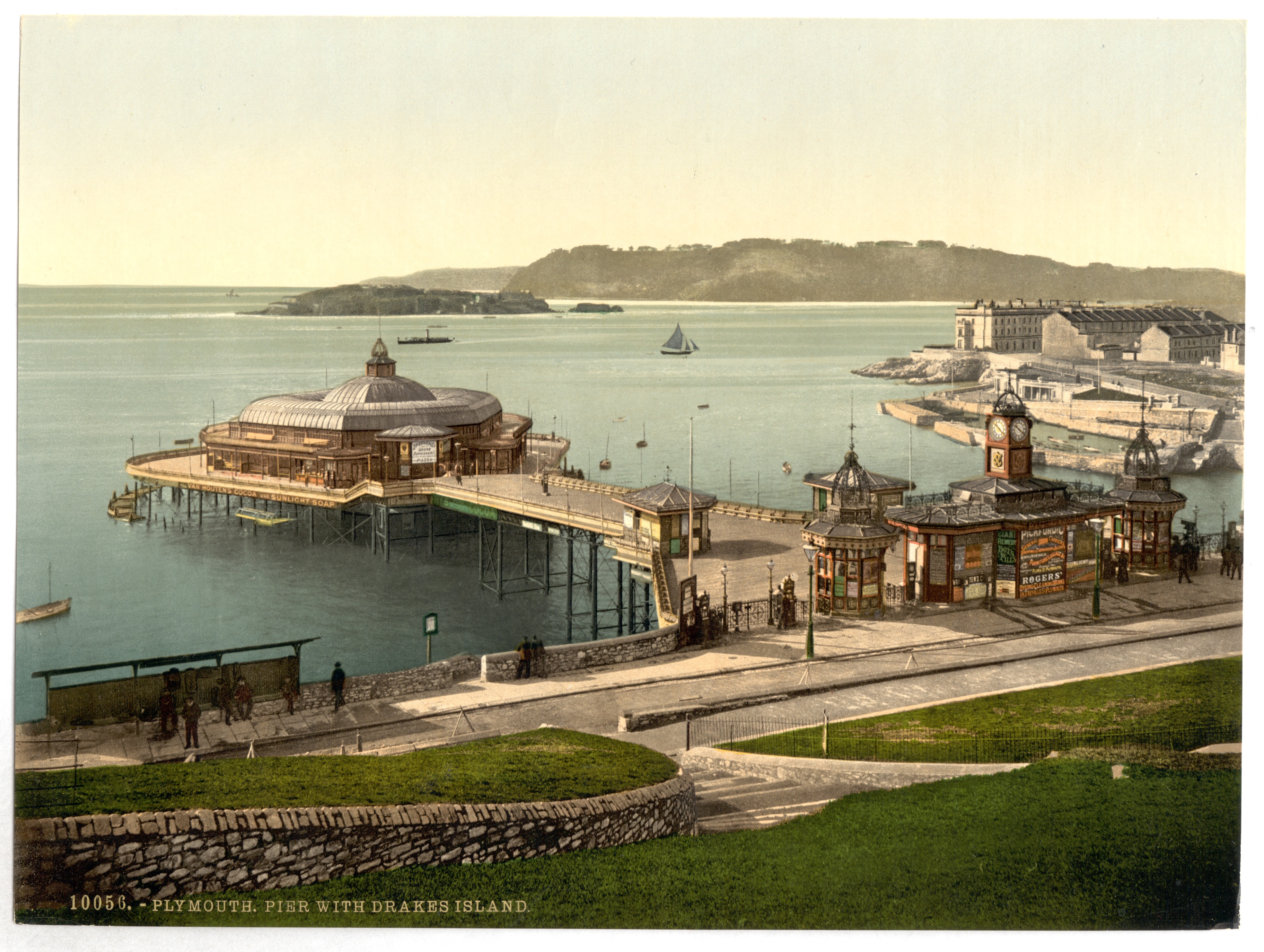

Plymouth {$plymouth}

Plymouth, England, 1904

Mozoomdar arrived in Plymouth on the morning of August 16. His spirits were high. With “a strange smell in the air that reminds one of antiquity,” PCM expressed to his wife how close he felt to God and his mission: “It is almost as if He is standing in front of me, the great Sage."37 The following day, he would sail across the Southern coast and dock in Tilsbury, London.

London

Having docked in Tilbury early in the day, Mozoomdar took a train to Freechurch Street (now Fenchurch Street Station) and then spent the next hour or so ambling by carriage to Highgate Hill, home of his longtime friend Reverend Robert Spears.

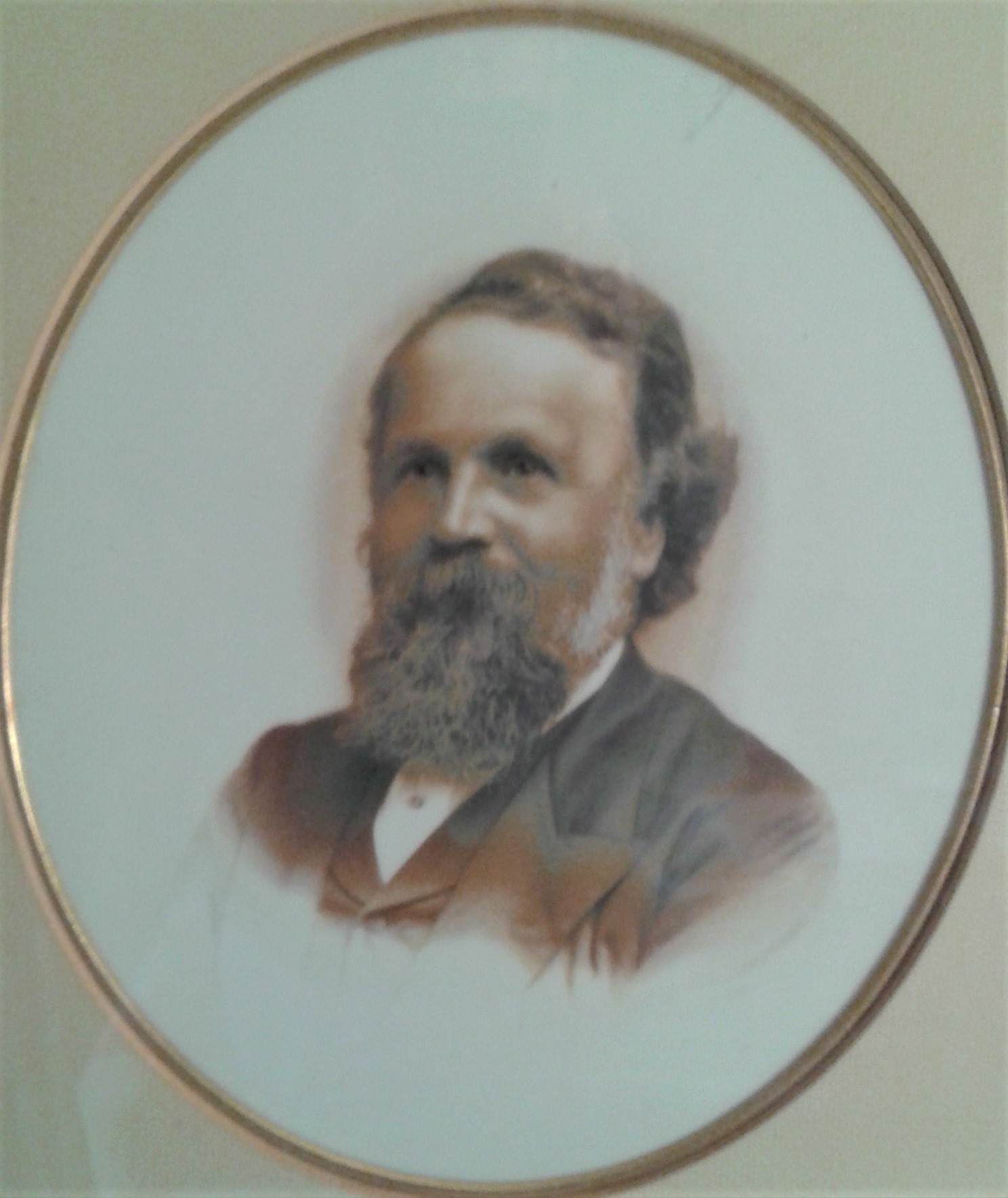

Reverend Robert Spears

Private collection of Malcolm Burns

The Unitarian preacher had hosted Mozoomdar during his visit in 1874, but moved to London’s northern suburbs in 1885 to found a girl’s school and a Unitarian church.38 PCM described the streets he saw on his way to Highgate as a scene of urban industry populated by shopkeepers, the cries of newspaper boys, crowds of businessmen, omnibuses, horse-drawn carriages, and tram cars “resplendent in painted advertisements from foot-board to coachbox."39

Mozoomdar shared in this spirit of industry. He preached at Spears' Unitarian church for Sunday-Monday services, and although morning attendance was thin, his evening mass drew a crowd.40 In addition, he gave an interview to the Reuter’s Agency, later reproduced in many of the daily and weekly papers, about the Bombay riots that took place from 11-14 August.41 Mozoomdar identified three causes of the riots:

(1) the agitation against cowkilling, (2) the belief among the Mohammedan community of Bombay that the sympathies of the Government are with them as against the Hindoos, and (3) the mixed and lawless character of the Mohammedan populace in Bombay.42

Though his characterization of Bombay Muslims may seem at odds with his aspirations for religious confraternity, PCM's perception of Islam as inherently violent did not prevent him from finding value in it. For example, in a Chicago lecture given three weeks later, Mozoomdar would maintain that Islam, “with fire and sword, proves the almightiness of God’s will."43

Liverpool

Amid his public engagements, Mozoomdar only managed to compose three letters to Saudamini in London. His writing reflects how he spent his moments of respite. Whether catching up with the Spears' at Arundel house, sitting amid the fruit trees of their garden, or chatting with B.B. Nagarkar, a Brahmo friend who would travel with him to Chicago, PCM had occasions to relax in good company. Yet his letters suggest that he was plagued with uncertainties during his brief moments of rest. Shaken by the discovery of a friend’s death in India, he wrote, “How can I be assured of anything after this?"44 Likely in an effort to shore up uncertainties regarding his own health, Mozoomdar redoubled his authoritative tone to Saudamini, demanding that she pray for him every day, finish her work, and prepare herself for heaven.45 Similarly, in a letter written the evening before his departure for the Liverpool Harbor, PCM assured Saudamini – and himself – that: “I am well. People in England told me that my features haven’t changed at all in these ten years. I don’t find that believable in the slightest, but so many people said this that it would have made you happy."46 Having thus attempted to comfort himself and his wife, Mozoomdar boarded the RMS Umbria bound for New York on 26 August.

Atlantic Ocean

Cunard Line Royal Majesty Ship Umbria, 1896

The Cunard RMS Umbria mesmerized Mozoomdar, who appears to have forgotten much of his anxiety during his week on the Atlantic. He wrote for The Interpreter that the ship was not so much a floating palace as a floating city, accommodating over 1000 passengers and personnel.

He spent his time amid sumptuous food, lavish salons, and lively galleries, complaining only that his quarters were “dark, stuffy, and overcrowded."47 Yet PCM had cause enough to occupy himself elsewhere. In the same article, he marveled at a close encounter with an iceberg seen off the starboard side, describing in detail how its proximity both figuratively and literally chilled those on deck.48 Perhaps the clearest evidence of his merriment is that Mozoomdar wrote only one brief note to Saudamini while on the ship. He reported good health, feeling refreshed by the sea air and free from seasickness, and mentioned a much warmer reception by these shipmates than he felt aboard the SS Khedive.49 Mozoomdar gave two lectures in the RMS Umbria’s galleries, each attracting hundreds of listeners who applauded him to the point of embarrassment.50 On 2 September, Mozoomdar greeted the shores of New York.

New York City

If the applause of his listeners aboard the RMS Umbria humbled Mozoomdar, the sight of New York once again inspired him to eloquence. Describing the harbor as “one of the most picturesque in the world,” Mozoomdar wrote of forested islands, the to-and-fro of ferries and barges, and “the mass of buildings, some of them fifteen stories high,” which gleamed against the cobalt sky.51 His stay in New York City was brief.

Plymouth Church, Brooklyn, 1904

On Sunday 3 September, he lectured for the congregation of the late Henry Ward Beecher, acclaimed preacher and abolitionist, who had died six years earlier. According to newspaper reports, Mozoomdar began his sermon with a reference to his 1883 visit, during which he had met Beecher himself. He then proceeded along a familiar refrain: “Do you want to know the profound thoughts in the mind of the Infinite? Look out before you on the face of nature, where on his right hand hath he scribed himself."52 PCM’s call for a turn toward nature would feature prominently in his parliament addresses as well. He thought that westerners in general, and Americans in particular, remained too occupied with labor and industry to see the spirit of God. In fact, he saw confirmation of this in the chalky complexions of New Yorkers, which he attributed to “overwork on the part of men, and metaphysics on the part of young ladies."53 Following his own advice, he left the following day – Labor Day – to enjoy the view of Niagara Falls before proceeding to Chicago.

Niagara Falls

The old great cataract set forth the same eternal roar, the whirlpool rapids rolled in their dark mysterious deeps, the heavy sprays kept up their region of perpetual showers and rainbows, and the strange noises rose, resounded and filled the heavens. The primeval forests still, gloomy, suggesting worship. The golden sun shorn of all his fierceness was setting with a sad dignity, the trees were almost human in their solemnity and awe. It was so full of God! O shall I ever come again.54

Likely excerpted from his diary, these reflections exemplify the type of divine wonder Mozoomdar sought to inspire in others. This was his second visit to Niagara, the first having been a decade earlier. His awe before the falls shows that they still impressed him greatly.

Period photograph of the Art Institute of Chicago, site of the 1893 World's Parliament of Religions

Chicago

At long last, nearly two months since his departure from Kolkata, Mozoomdar reached Chicago. Although cheerful upon his arrival, convinced that everything he saw at the World’s Fair was graced with God’s presence, PCM soon became disheartened by lack of news from Saudamini. In the first of several letters written to her in Chicago, he attempted to console himself by insisting that despite his longing to see his wife, she “wouldn’t have been able to tolerate the journey” and therefore rightly remained in Kolkata.55 Yet his despondence worsened as the beginning of the parliament approached. On the evening of September 10, hours before the conference would begin, he wrote:

I feel lonely and tired. I wondered why I haven’t received your letters yet. Then I saw your handwriting. I feel numb and absent-minded. Write to me. Write anything. Whatever you write will be good for me. It will calm my mind, and also be good for you. Can’t you write a few lines to the one for whom you have done so much? I want to scold you, but my eyes tear up instead…. I think about you a lot. I don’t know whether you think of me. Heaven will mean nothing to me if I’m there and you aren’t. I will pray for hell, then…. I await your hopeful voice in this foreign land. Don’t hesitate to make yourself known.56

It was not until over a week later that the longed-for letter arrived, postmarked 9 August. Preoccupied with the proceedings of the World’s Parliament of Religions, PCM’s response indicates that he was impatient with his wife’s brevity, feeling too busy himself to write everything down.57 He also had doubts about his ability to keep in touch with her during the remaining three months of his stay in the US. These doubts appear to have been well-founded, for the final letter in the series ends mid-sentence: “I should have addressed all my letters via Spears, because I don’t know how they will be delivered if I change my address. And my American address…"58

Denoument

No records remain of Mozoomdar’s correspondence with Saudamini after his departure from Chicago. One reason for this, and also perhaps for his feeling “numb and absent-minded,” is that Mozoomdar’s health declined rapidly during the course of his three-week stay there. By the close of the World’s Parliament of Religions, PCM was diagnosed with diabetes and forbidden to work. Yet his sense of duty to his divine task both forbade him from heeding his doctor’s advice and prevented him from writing home about his condition.59

Mozoomdar surely felt pressure to perform well at the World’s Parliament of Religions, not only to justify his travel to the West, but also to validate his hopes that the New Dispensation could flourish there. It is to his credit that little of PCM’s personal problems surface among his speeches in Chicago.60 Accounts of his addresses depict Mozoomdar at his best. For example, the Christian Register, a Boston paper edited by John Henry Barrows, the chief organizer of the World’s Parliament of Religions, proclaimed:

No voice commanded more attention or more sympathy at the Parliament of Religions than that of the prophet of the Brahmo-Somaj. Upon no one in the Pentecostal gathering did the cloven tongue of fire more surely rest [than on] Mr. Mozoomdar.61

Further evidence rests in the transcriptions of his speeches, though it is beyond the scope of this exhibition to detail these parliament lectures. Rather, this chronicle has been meant to provide the intimate and seldom-considered details of PCM’s hopes, fears, and experiences during his sojourn from Kolkata to Chicago. Mozoomdar was eager to travel yet homesick, publicly ebullient yet privately ill, anxious of failure yet inspired by God. This personal context, much more than the history of British colonialism or even the controversies of Keshub Sen, holds the key to understanding most fully his addresses in Chicago and his broader religious vision.

Despite failing health, Mozoomdar continued to lecture in the US until early December, spending most of his time in Boston. In total, he was said to have delivered almost 200 lectures during his three months in the country in 1893.62 His efforts bore fruit. Immediately after the World’s Parliament, John Henry Barrows began an effort to provide PCM financial support. In December 1893, this resulted in the Mozoomdar Mission Fund, which allowed PCM to visit the US once more in 1900.63 In October 1894, Caroline E. Haskell gave $20,000 to the University of Chicago in order to establish an annual lectureship in Kolkata. She did so as a direct response to a wish that Mozoomdar had penned to Barrows earlier that year64

These and other developments kept PCM active until the summer of 1904, when his health began to decline sharply. Though his diabetes was under control, he had contracted tuberculosis, and his deteriorating condition confined him to his bed by December.65 Despite this, PCM spent the final six months of his life in earnest devotion: his friend and biographer Suresh Chunder Bose described it as “the conquest of the love of God over sickness and death."66 Mozoomdar died in his Kolkata home on May 21, 1905, in the company of Saudamini and under the watchful gaze of Debendranath Tagore and Keshub Sen, whose portraits hung on the wall nearby.67 Though he cannot be said to have fully realized his ambitions for the Brahmo Samaj, Mozoomdar died at peace, in the company of loved ones, ready for union with the divine. Perhaps the two epitaphs inscribed on his monument, written in his own words, express this best:

I have done the work that was given to me, I have kept the vow I took. I have struggled to unfold my message to many men and women. Peace fills my soul. For all opportunities and facilities, yea for discouragements and depressions, I have the heart to be grateful to God. His ways are not our ways, nor His purposes our purposes. But He has amply proved to me this His great dispensation of the Spirit is sure some day to be the faith of mankind. Blessed forever be His name.

I have gained thee with very little spiritual culture, while living this lowly life on earth. Now I start on my way to gain Thee in a degree beyond all measure.68

-

Sunrit Mullick, The First Hindu Mission to America : The Pioneering Visits of Protap Chunder Mozoomdar (New Delhi: Northern Book Centre, 2010), 95. ↩︎

-

P. C. (Protap Chunder) Mozoomdar, ed., “Rev. P.C. Mozoomdar’s Departure for America.” The Interpreter 2, no. 1 (1893): 2. ↩︎

-

Suresh Chunder Bose, The Life of Protap Chunder Mozoomdar (Calcutta: Nababidhan Trust, 1927), 33–41. ↩︎

-

Mozoomdar, “Rev. P.C. Mozoomdar’s Departure for America.” 2. ↩︎

-

P. C. (Protap Chunder) Mozoomdar, Letters Written by Protapchandra to His Wife, ed. Nick Tackes, trans. Subhranil Roy, 2018, 1. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 3. ↩︎

-

Hunyadi János was a Hungarian aperient spring water that gained popularity in the 1860s. See Hunyadi János: Natural Purgative Water Drawn from Saxlehner’s Bitter-Water Springs Near Budapest. (Budapest: Firm of A. Saxlehner, 1898). ↩︎

-

Mozoomdar, Letters Written by Protapchandra to His Wife, 9. ↩︎

-

Mozoomdar would later spell out these sentiments before the World’s Parliament of Religions in his lecture titled “The World’s Religious Debt to Asia.” See P. C. (Protap Chunder) Mozoomdar, Lectures in America & Other Papers. (Calcutta: Navavidhan Publication Committee, 1955), 15–29. ↩︎

-

Mozoomdar, Letters Written by Protapchandra to His Wife, 11–12. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 12–13. ↩︎

-

In the context of the passage, this vrata or vow likely refers to maintaining a lifestyle of overall austerity for the benefit of not only the vow-taker (in this case, Saudamini), but also her husband. Such vows were common obligations of Bengali wives at this time. See Judith E. Walsh, Domesticity in Colonial India : What Women Learned When Men Gave Them Advice (Lanham, Md: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2004), 36. ↩︎

-

Mozoomdar, Letters Written by Protapchandra to His Wife, 18–19. ↩︎

-

Although the Brahmo Samaj meant to improve the lives of women through their reforms, they never intended to free women from the domestic obligation of serving their husbands. See Walsh, Domesticity in Colonial India, 42–46. ↩︎

-

Mozoomdar, Letters Written by Protapchandra to His Wife, 17–18. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 13–15. ↩︎

-

P. C. (Protap Chunder) Mozoomdar, ed., “The Raging Sea,” The Interpreter 2, no. 1 (1893): 27. ↩︎

-

Mozoomdar, Letters Written by Protapchandra to His Wife, 19–20. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 20–21. ↩︎

-

Bose, The Life of Protap Chunder Mozoomdar, 114–15. ↩︎

-

P. C. (Protap Chunder) Mozoomdar, ed., “Red Sea, Why Red,” The Interpreter 2, no. 1 (1893): 27. ↩︎

-

Mozoomdar, Letters Written by Protapchandra to His Wife, 21. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 16. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 22. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 25. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 26. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

P. C. (Protap Chunder) Mozoomdar, ed., “The Organization of a British Ship,” The Interpreter 2, no. 1 (1893): 29. ↩︎

-

Mozoomdar, Letters Written by Protapchandra to His Wife, 30. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 13. Mozoomdar’s association of a ruddy complexion with health and beauty is a refreshing inversion of contemporary “fairness” campaigns in the cosmetics industry. ↩︎

-

P. C. (Protap Chunder) Mozoomdar, ed., “On the Way to Chicago,” The Interpreter 2, no. 1 (1893): 48. ↩︎

-

Mozoomdar, Letters Written by Protapchandra to His Wife, 32. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 33. ↩︎

-

Mozoomdar’s lack of means stemmed from his decision to work, without compensation, for a Brahmo Samaj newspaper and his estrangement from family, which resulted in the partial loss of his inheritance. See Bose, The Life of Protap Chunder Mozoomdar, 22–30. ↩︎

-

Mozoomdar, Letters Written by Protapchandra to His Wife, 35. ↩︎

-

Alan Ruston, “Robert Spears - the Unitarian Dynamo,” Transactions of the Unitarian Historical Society; London 22, no. 1 (April 1999): 54–67. ↩︎

-

Mozoomdar, “On the Way to Chicago,” 48–49. ↩︎

-

Mozoomdar, Letters Written by Protapchandra to His Wife, 48–49. ↩︎

-

These riots were ostensibly caused by Hindu-Muslim disputes over cow-slaughter, and came to be represented as one episode in a series of outbursts of communal violence leading up to Indian Independence. See Jim Masselos, “The City as Represented in Crowd Action: Bombay, 1893,” Economic and Political Weekly 28, no. 5 (1993): 185. ↩︎

-

“An Indian Pundit on the Bombay Riots,” The Nottingham Evening Post, August 1893, 4. ↩︎

-

Mozoomdar, Lectures in America & Other Papers., 12. ↩︎

-

Mozoomdar, Letters Written by Protapchandra to His Wife, 38. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 39–40. ↩︎

-

Mozoomdar, “On the Way to Chicago,” 50. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Mozoomdar, Letters Written by Protapchandra to His Wife, 41–42. ↩︎

-

Mozoomdar, “On the Way to Chicago,” 51. ↩︎

-

Mozoomdar, Letters Written by Protapchandra to His Wife, 51–52. ↩︎

-

“A Hindu in Plymouth Church,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 1893, 7. ↩︎

-

Mozoomdar, “On the Way to Chicago,” 52. ↩︎

-

Bose, The Life of Protap Chunder Mozoomdar, 176. ↩︎

-

Mozoomdar, Letters Written by Protapchandra to His Wife, 44–45. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 46–47. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 49–50. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 51–52. This abrupt ending marks the end of the final extant page of the preserved letters, and suggests that all subsequent pages have been lost. Though Mozoomdar’s health was poor, nothing indicates that he stopped writing during his remaining time in the US. Unfortunately, no records of Saudamini’s letters to PCM exist.". ↩︎

-

Bose, The Life of Protap Chunder Mozoomdar, 185. ↩︎

-

This is not to say that his failing health was lost to his friends. Correspondence between John Henry Barrows and Jenkin Lloyd Jones indicates that the latter believed Mozoomdar would soon succumb to Bright’s Disease. See Jenkin Lloyd Jones, “Dec. 15, 1893,” Letters to John Henry Barrows, 1893, 403. ↩︎

-

P. C. (Protap Chunder) Mozoomdar, ed., “Babu Protap Chunder Mozoomdar,” The Interpreter 2, no. 4 (1893): 80. ↩︎

-

Bose, The Life of Protap Chunder Mozoomdar, 202–3. ↩︎

-

Mullick, The First Hindu Mission to America, 138. ↩︎

-

These lectures continued until at least 1961. ibid., 210. ↩︎

-

Bose, The Life of Protap Chunder Mozoomdar, 360. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 371. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 375. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 376–77. The second of these is an English translation from Bengali. It is unclear whether Mozoomdar’s monument still stands. ↩︎